Machines, AI, and the Most Important Question in the World

Message from 2024: I wrote this post in the spring of 2023, as AI tools were pretty new. I’ve since landed on the principle of not using AI generated images on my blog. This post has two images like this, but as it’s critical of the models (and explains a bit of why I currently don’t want to use them), I’ve let them be.

First, a very simplified history lesson:

For a large portion of the human existence, technology (often in the shape of machines or tools) has replaced manual labour, and led to increased productivity. The printing press replaced monks writing books by hand, looms evolved to include less and less manual laber per unit of fabric, the telegraph reduced the need for mail carriers, and photography really hurt Big Portrait Painting. Usually, the technology doesn’t completely replace the professions it affects. For instance, you can still get a tailored suit – but it’s a minor part of the clothing industry, and mostly reserved for the wealthy. The old turns into niches, hobbies, crafts and/or art.

Here are some of the positives from this:

1) There are new jobs created within those industries.

People need to build, repair and operate the machines. We lose portrait painters, but gain photographers. However, how meaningful, healthy and fair paying are these jobs?

2) The increased efficiency reduces costs of goods and products, making them accessible to a larger portion of the population.

The Motorola DynaTAC 8000X went for $3.995 (equivalent to over $10.000 today) in 1983, while the Google Pixel 6A goes for like $350, and can obviously do a lot more. Progress has not only given us more comfort and entertainment, but also greatly increased life expectancy. (But reduced prices has also increased our consumption to unsustainable levels. This dilemma warrants its own article, that I’ll write later!)

3) People having more time (and money) on their hands, creates jobs we «didn’t have time for» earlier.

The first example of this, was with the agricultural revolution. Before this, everyone had to be hunters and gatherers, as one person couldn’t create much more food than to feed themselves. When we got farmers, a portion of the population could do other stuff than getting food. This created specialisation and professions, and allowed us the time to create stuff like cities and organised religion. The amount of dog groomers and interior designers correlate with the amount of excess in a society.

The Artificial Revolution, and unintended consequences

Now, I’ve no basis of saying the advent of AI will have the same impact on society as the Agricultural or the Industrial Revolution (perhaps a closer analogy would be the wide adoption of the web). However, there are some lessons to be learned.

AI will become a large part of society – both in our work and personal lives. And just like industry, it brings with it unintended consequences that we need to deal with – even removed from questions about economics and ethics. With industry, one of the most important side effects was the environmental impact. Not only did we fail to anticipate that problem – we are still failing miserably to deal with it properly. Let’s hope we won’t repeat the same mistake with AI, regardless of what problems it’ll bring.

The ethical quirks of generative AI

The creation of AI tools for things like writing and imagery, has something that separates it from most other disruptive technologies: The works and intellectual property of the workers and creators it’s designed to replace, is essential for the technology to work. Microsoft’s new version of Bing is a good example:

The search engine wants to give you answers directly, so you don’t have to visit other sites. **But it wouldn’t be able to give you these answers if it weren’t for the fact that it’s scraped those same sites for information. **

It’s the same with image generators: The only reason I can make Stable Diffusion create an image in the style of an artist, is that the model has been trained on the works of the exact artist I now don’t have to hire. And the artist had no say in this.

The laws of today are relevant to the legal cases that run presently. But it’s not relevant to the ethics, and not to laws adapted to an AI inhabited reality. These laws should say that you can’t use artist’s work to create these tools without the three C’s:

- Consent,

- Credit and

- Compensation.

Consent, Credit and Compensation. If you can’t make the tool work in a way that artists get sufficient credit and compensation, then you probably won’t get their consent. And then the technology simply shouldn’t be available.

So while technology has replacing manual labour countless times, and will continue to do so (also in creative professions), I do think these tools has some special ethical considerations.

We also need to be very vigilante about who gets the benefits of the increased productivity, and who gets left behind

There’s been talk about AI «taking our jobs» for a while – truck drivers are one example. Now, it might take longer than Elon Musk thinks (or at least says), but it’s still understandable that truck drivers are worried about their livelihood. And while technology creates jobs (as well as destroying them), are the new jobs suited for the people it displaced? There are larger changes over fewer generations now, compared to previous revolutions. Technology moves fast, but humans remain pretty sluggish pieces of meat.

Maybe the most important question in the world

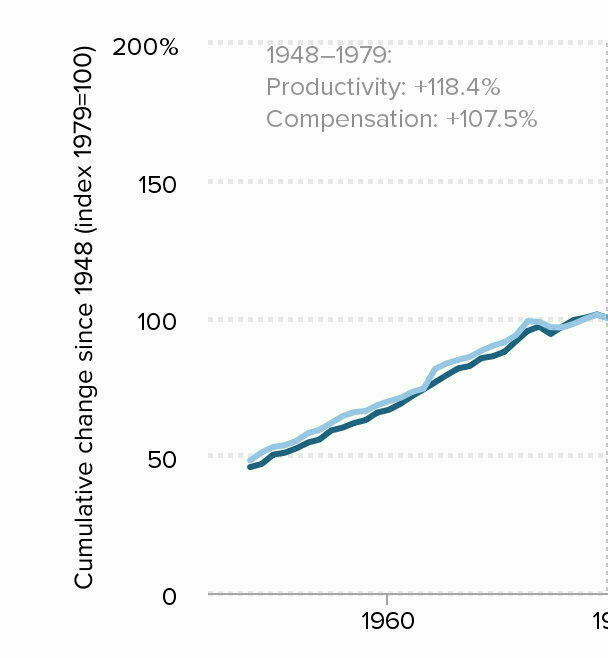

The statistics that compare productivity and worker’s compensation in the USA is one of the most revealing statistics I know. The dark line shows the productivity, and the lighter one the typical worker’s compensation. Here’s the graph from 1948 to 1979:

As the amount of value workers generated increased, their pay increased as well. (Keep in mind, the employer increased their profits as well.)

But let’s take a look at the continuation:

At the start of the 1980s, something happened, that made most of the increased profits from higher productivity go elsewhere. (Now, I don’t have a problem with some people getting rich. But I do have a problem with how rich some people get, and how much it is at the expense of the planet and people having less than them.)

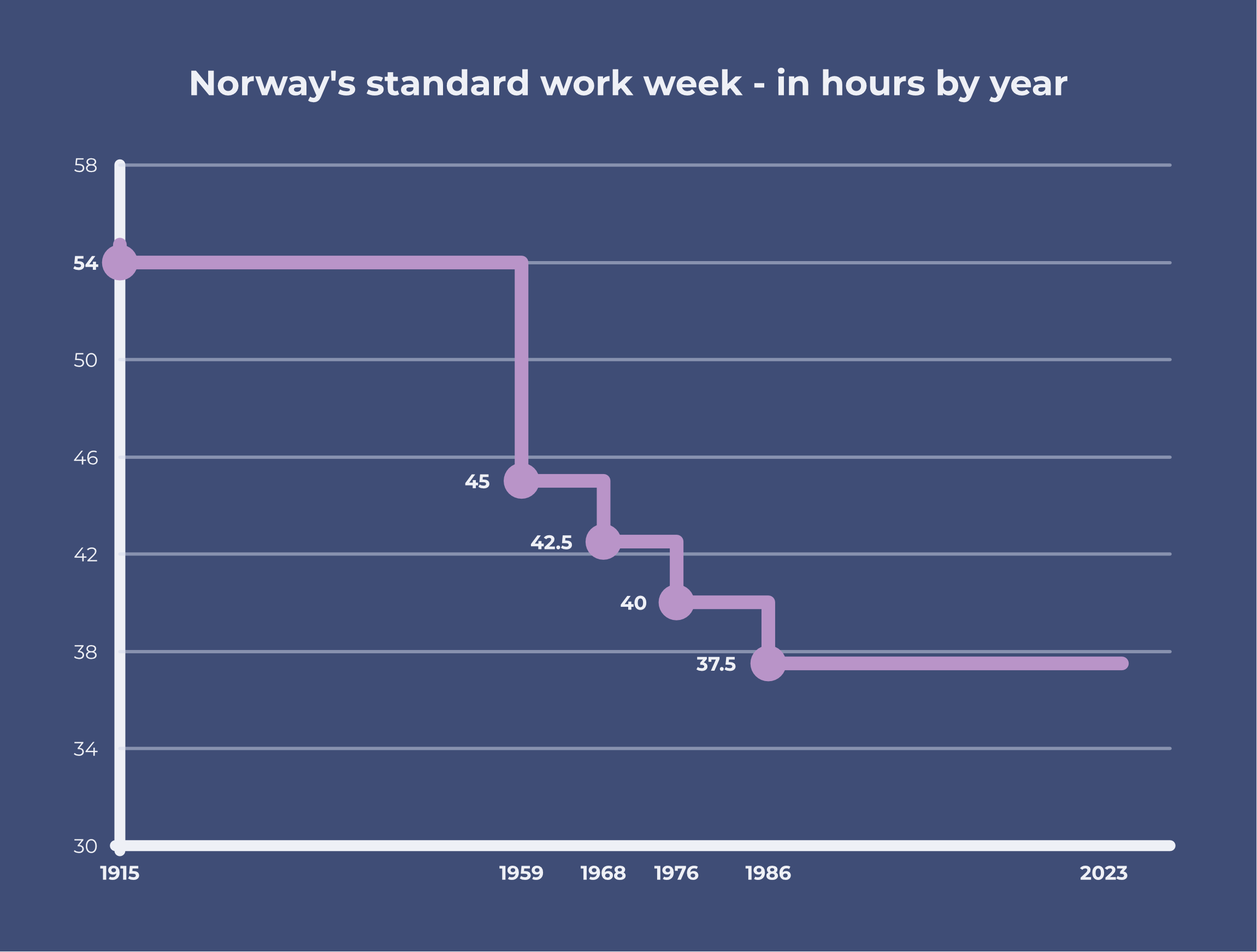

Let’s take a look at a development in Norway, the standard workweek.

In 1915, the standard workweek was set to 54 hours. It’s since been decreased several times, the last time in 1986 (to 37.5 hours a week, 7.5 hours a day).

This brings me to the teased question, that I genuinely think is (at least one of) the most important questions in the world:

How do we «spend» the gains of increased productivity?

So while you could say that progress and increased productivity is inevitable, who benefits from it is very much a matter of intentions, power, and politics. A classic argument from people who don’t think we need to do something about the rampant inequality, is that we’ve made great progress in living standard all over the world. And while this is true, the most relevant comparison isn’t 1923 to 2023 – but our 2023 to a theoretical 2023 where we’ve distributed wealth better. The history of the working class in America (and many other places), shows how increased productivity can benefit only a few.

The reason I brought up Norway, is that we’ve shown that it’s possible to convert the increased productivity into something besides wealth: time.

The reason this question is so important, is that it touches two of the largest challenges we face: Climate change and inequality. We need to make sure that everyone benefits from the increased productivity, and value, technology provides. But we also need to withdraw this value as time, and not only wealth.

Even though I might sound very negative to both technology and AI, that’s not the case. If we look at the smartphone: That «everyone» has access to communication, information, entertainment, cameras and much more, at all times, is remarkable. And I truly belive that AI can do fantastic stuff for creativity and humanity in general. However, we can’t let this appeal blind us to the ethical problems found in its conception or the way it can further concentrate power and wealth.